Language Learning: 7 reasons to use a dictionary

Dictionaries are bulky, heavy, cumbersome, slow, and awkward. Not to mention expensive, at least here in Germany.

And who needs dictionaries these days anyway since we have Google? So much easier and faster to just look up words online, right?

We all pretty much know that just because something is easier and faster, doesn’t necessarily mean it’s also better. Getting something from a fast-food joint is easier and faster than cooking a meal, but it’s not optimal nutrition.

I do look up a lot of words on my phone, but I couldn’t even imagine trying to learn a new language without a real paper dictionary, and here are 7 reasons why:

Find useful words that are not in your textbook

You can chance upon all kinds of useful words just paging through the dictionary. Words that you would use in your daily speech but that aren’t in your textbook or haven’t come up in class. You look up the word for “word” in German and find not only “Wort” but all of the related words such as “Wortschatz” (vocabulary – literally it means “word treasure” – I love that!), “wörtlich” (literally) and “Wortspiel” (play-on-words; pun) The basics are all there, in one place, like gold coins in a treasure chest. Isn’t that convenient? Besides, everybody has different interests and since you might want to talk about motorcycles, quilting, or marine biology in your new language, words related to these interests are unlikely to be found in a generic textbook. And the more personalized you make your learning, the more interesting it will be.

366 Days of Wisdom from Robert Greene

The Daily Laws

by Robert Greene

Today I’m recommending a book I’ve barely even started reading.

But I have a good excuse for that.

It’s written by the wise and wonderful Robert Greene.

If you’ve read anything by Robert Greene, you know what I mean. And if you haven’t, you’re in for a treat.

The Daily Laws is set up much like The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman. There is a short essay for each day of the year and something concrete to think about and each month has a theme.

Greene is fearless and doesn’t mince words. He gets to the core of human behavior, the stuff we don’t like to think about too deeply because it’s uncomfortable. He often points out how devious and manipulative people can be and it’s helpful to learn how to recognize that. But reading or listening to him also makes you feel more compassionate towards humans in general (including yourself) because we’re all flawed in some way, we all tell ourselves lies, and if you’ve ever had this vague feeling that much of what you see or hear out there isn’t quite as shiny as it looks, that’s because quite often it’s not. And there’s something weirdly comforting about knowing that too.

In the preface Greene writes that The Daily Laws is designed to reverse the toxic patterns we’ve become trapped in, reconnect us to reality, and to attune our minds to the most entrenched traits of human nature and how our brains operate.

I started The Daily Laws about two weeks ago, on November 17. November’s theme is The Rational Human. Realizing Your Higher Self and December’s essays, The Cosmic Sublime. Expanding the Mind to its Furthest Reaches, include thoughts from his upcoming book on the Sublime.

Considering how often we make snap judgments about people based on a single action or statement, the essay for November 27th was really one to think about. It was titled “Assume You’re Misjudging the People Around You.”

At the bottom of each daily essay/thought is the title and chapter of the book it came from, in case you want to delve more deeply into a certain topic.

It seems to me that there are lots of really smart people out there, but very few who are wise. Robert Greene is one of those exceptions.

The 50th Law by 50 Cent and Robert Greene

The 50th Law

By 50 Cent and Robert Greene

How to be bold and fearless, innovative and determined, and grounded in reality?

There is a lot to learn from The 50th Law by 50 Cent and Robert Greene even if you’re not aiming to be a hip hop entrepreneur.

Fear and anxiety rule our lives in many ways and not just in the physical sense. We fear saying the wrong thing and maybe offending someone. We fear change, conflict, and uncomfortable discussions. Making decisions and taking responsibility. We fear being somehow different from the rest of the herd.

One quote by 50 Cent in the book starts off with this sentence:

“The greatest fear people have is that of being themselves.”

And if you think about this for a bit, you will realize how true that is. And how odd we humans really are in that way.

So The 50th Law is partly a manual on how to cultivate courage and fearlessness in your own life.

It is divided into ten chapters that address different spheres of fears, interwoven with anecdotes from 50 Cent’s life, from his days as a hustler to his success as a singer and entrepreneur.

Robert Greene is an absolute master at explaining human behavior with examples drawn from history and he distills it into understandable and implementable strategies that can be used in daily life. He’s done all the research and laid a solid foundation for the reader to think about. He asks questions and makes observations that might make you squirm though, because he sees through all the bullshit we tell ourselves.

For example, one of the chapters is about finding opportunity in everything that

happens. If 50 Cent was able to find opportunity in getting shot nine times and nearly dying, then what excuse do I have? I still have so much to learn.

Other chapters delve into topics such as being intensely realistic, the importance of being self-reliant, knowing and connecting with your environment, mastering skills, and confronting your own mortality. Deep issues that affect everybody on some level.

I bought The 50th Law for my son Max who is a musician* and in many ways has already cultivated more fearlessness than I have, but you don’t have to even

like hip hop or rap to love this book. Sorry Max, I read this before I wrapped it up for your birthday—but I guess you won’t be really surprised to hear that…

*look for Moodsphinx on Spotify (two of my favorite songs of his are “Entzug” and “It’s Cool to Cry”)

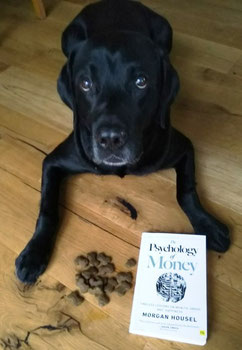

The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel

The Psychology of Money.

Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness

By Morgan Housel

Finance books are not my normal reading fare (although they probably should be), and I bought this one mainly because the word “psychology” was in the title.

The Psychology of Money is a great book and it’s easy to read. You don’t need a degree in economics or have to know anything about the stock market to understand the lessons here. But even two people I know who seem to devour every finance book on the market and who do know a lot about the subject were impressed with Housel’s book.

After reading it, I ordered more copies and so far have given this book to five people, four of them under 30-year-olds, because this is something I wish I would’ve read and thought about more when I was young.

The Psychology of Money is divided up into nineteen short chapters, each with a lesson about money, and because they are often counterintuitive, they will make you pause and think. At the end is a brief history of why American consumers think the way they do, which was also somewhat enlightening. Housel’s point of view is that the so-called soft skill of psychology is more important than the technical sides of money.

Here are just some of the things you will learn:

Why nobody is crazy—at least in terms of how they think about and handle money. Remember that p-word in the title…?

About luck, risk, and greed, and how some people really do need to be told that if they spend more money than they have, then they will not end up wealthy.

How amazing compounding really is. This is a hard concept for the human brain to grasp, but Housel explains this too.

Why we can hope to only be pretty reasonable rather than totally rational about money, and that’s okay. We’re human after all.

How you can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune and the difference between getting wealthy and staying wealthy.

Speaking of which…

Housel starts the book with a story about Ronald James Read who fixed cars and worked as a janitor before dying in 2014 at the age of 92.

“So what?” you may ask.

Right. Well the interesting part is that he left an inheritance of $8 million when he died.

Housel also has a great website with loads of articles:

And for a fun 15-minute animated review of the book:

The Swedish Investor’s YouTube video

Silverview by John le Carré

Silverview

By John le Carré

Julian is a 33-year old former trader who has given up his London flat, Porsche, and party life to open up a bookshop in a small seaside town even though he knows absolutely nothing about books.

Soon after his arrival, Edward comes into the shop and a few pages of dialogue later, you are left wondering...

Who is Edward, really?

And what does he want from Julian?

But to quote Forrest Gump: that’s all I have to say about that.

Because that’s all you need to know. It’s a le Carré novel after all.

So you already know there are spies and twists and turns, and that things aren’t always what they seem at first glance, and is Edward even his real name?

The dialogues in Silverview are brilliant. There is one long scene where Proctor, an agent, visits two former agents who used to work with Edward to find out about Edward’s past that is such delicious reading that it alone is worth buying the novel for. Because Proctor, naturally, doesn’t tell the two exactly why he needs this information either and so he has to make up a story to frame this interview too.

In some ways Silverview feels almost like a sketch of a novel, as though it wasn’t quite finished. It was published posthumously (John le Carré died in December 2020) and came out just a few weeks ago, so maybe that’s why. It’s very short, only 208 pages, and there’s also a melancholy, almost wistful feeling about it, but that may be due partly to the fact that I knew it was the last work we’ll read by probably the greatest spy novelist ever.

Canada Guest of Honor at Frankfurt Book Fair 2021

Who would’ve thought that I would miss the shoulder to shoulder crowds shuffling slowly through Hall 3 where the big publishers show their books? The hot sticky air that comes from thousands of people crowding around the latest publications. The long lines to get lunch or coffee or to use the women’s room.

This year the Frankfurt Book Fair had fewer visitors, fewer publishers, fewer books, and it was less international. It felt rather subdued, sedate, and calm.

So even though I was overjoyed that the fair took place this year, I missed that hustling, bustling buzz, that crackle of excitement that is normally in the air. And I felt bad for Canada, the Guest of Honor. First the book fair was cancelled in 2020 and even though they had a pavilion this year, I don’t think they quite got to experience the usual vibe of this fabulous book fair.

Still, it was one performance by a Canadian hoop dancer that drew a crowd on Sunday afternoon and exuded the magic that was missing elsewhere on the grounds. Dallas Arcand (aka DJ Krayzkree) held an audience spellbound and his last performance was a wild blend of traditional and electronic music. After looking him up I discovered that he is world-renowned and has performed at the 2010 and the 2012 Olympics. Take a look at his website since I was too mesmerized to take a photo during his performance.

Here is a list of a few books on display at the Canadian pavilion that caught my eye and that I jotted down in my notebook:

The Innocents by Michael Crummey

Survival by Margaret Atwood

A Trio of Tolerable Tales by Margaret Atwood

Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage by Alice Munro (Apparently a book of short stories for people who don’t usually like short stories much. That would be me.)

Le Grand Nord-Ouest by Anne-Marie Garat

Madeleine Thien (multiple books)

Fifth Business by Robertson Davies

À train perdu by Jocelyne Saucier

American War by Omar El Akkad

Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown

Keeper ‘n Me by Richard Wagamese

The Last Neanderthal by Claire Cameron

Crow Lake by Mary Lawson

By Gaslight by Steven Price

Volkswagen Blues by Jacques Poulin

Inspector Gamache mystery series by Louise Penny

And the one that stood out most because of the gorgeous photographs:

Blanket Toss Under Midnight Sun. Portraits of Everyday Life in Eight Indigenous Communities by Paul Seesequasis

Roget's International Thesaurus

Roget’s International Thesaurus

(Seventh Edition)

Edited by Barbara Ann Kipfer, Ph.D.

Something essential was missing from my life for years but I wasn’t sure exactly what. It was only after I’d written a novel that I realized what that was.

A good thesaurus.

I wish I’d discovered Roget’s International Thesaurus much earlier because looking up synonyms on the internet is okay now and again but it’s far from an ideal method.

When I mentioned this to my sister Marjaana during a zoom call, she didn’t hesitate for even a second. Buy Roget’s. The Seventh Edition. And, yes ma’am, I did, because she’s a copyeditor and knows what she’s talking about when it comes to these things.

Turned out to be one of the best buys I have ever made.

I can literally get lost in Roget’s Thesaurus. I look up one thing and it leads to another and I can pore through the pages for ages. When I first leafed through it, I had an inkling of how Gollum must’ve felt when he found the ring.

No matter what kind of inkslinging you do (and everybody writes, pens, or scribbles something), this is a valuable resource. It’s not only helpful, practical, and applicable, but also functional and reusable. Anything but dry, dusty, barren, or banal, and sometimes the words you find will even make you giggle, chuckle, chortle, cackle, and crow.

Use it to pepper, stud, or sprinkle your text with color. Maybe cranberry, ginger, cinder, cerise, amethyst, or mulberry? And what on earth is Paris green?*

I love the way it’s organized into categories of general ideas. These include The body and the senses, Feelings, Natural Phenomena, Behavior and the Will, Sports, The Mind and Ideas, and many more. There are lists of cheeses, colors, boxing punches, manias, and spacecraft, artificial satellites & space probes. There’s even a list of acceptable two letter Scrabble words.

Thesaurus apparently means “treasury” or “storehouse” and Roget’s truly is that.

1282 pages that will make you feel loaded, prosperous, and filthy rich, pockets lined

with a wealth of words and phrases. You can roll and wallow in synonyms, antonyms, and archaisms and express yourself with terms that are polished, refined, and elegant, or raw and coarse and

crude, according to your mood.

And don’t be surprised if you find yourself clutching it and murmuring something that sounds vaguely like “my precious” while stroking the cover. I’m sure that’s nothing to be worried about.

*Turns out that Paris Green was an emerald-green powder that was used not only as a pigment but also to kill off insects and rodents because it was highly toxic. Also “involved in poisoning accidents,” according to Wikipedia.

Natasha's Dance. A Cultural History of Russia by Orlando Figes

Natasha’s Dance. A Cultural History of Russia

by Orlando Figes

Natasha’s Dance is a spectacular, fascinating, intelligent, and in places, a very touching piece of work.

Although it is about Russian cultural history, it often felt more like a psychological and philosophical study of the “Russian soul” throughout the centuries. As if Russia had been lying on a couch and was being analyzed by various artists, intellectuals, nobles, serfs, and statesmen who were all trying to figure out who she was exactly, what she wanted, and how she wanted to be seen in the world. Existential questions, really.

From Peter the Great who founded St. Petersburg in 1703 and wanted Russia to be more European to the horrific years of Stalin’s terror and then up to the 1960’s.

This is a huge subject and just the amount of research that must have gone into this 586 page book (plus notes and lists for further reading) is awe-inspiring. Orlando Figes covers big themes and cultural movements, much of it through the eyes of painters, writers, and musicians. I learned so much that I wouldn’t even know where to begin listing it all, but I was fascinated by the customs he describes throughout the centuries, both those of the nobles and the peasants.

Details and anecdotes give life to the pages and there is even a shopping list of all the things one nobleman wanted to have imported from Europe in the late 18th century, which included things like 240 pounds of parmesan and 24 pairs of lace cuffs for nightshirts. Only 12 pounds of coffee from Martinique though. I thought that a bit meager, considering how many pounds of coffee we drink in this household and we’re not in the habit of holding balls for thousands of people.

A section titled “Descendents of Genghiz Khan” starts off with Kandinsky’s travels to a remote Komi-region in 1889 to study Finno-Ugric beliefs because he thought he might want to become an anthropologist before he became an artist.

The bits about Tolstoy were also especially interesting as he seemed to be torn between

wanting to live a simple peasant life yet he enjoyed the luxuries of his large estate (funnily enough, Tolstoy himself would make a great character for a novel!) and Chekhov was one of my

favorites; I definitely want to read his works and also more about his life now. So you see, Natasha's Dance is kind of like a drug for those of us with a slight

addiction to books and reading—it just makes you want more of the same…

Natasha’s Dance is just the kind of history book I love. It’s so captivating and well written that I was literally immersed in a different world, much like what happens with a really good novel. Many a household chore was left undone because I thought I’d read just a few pages before getting to work… Now I’m excited to read even more, but first I’ll have to page through Natasha’s Dance again to take another look at the dozens of passages I’ve marked with little sticky notes.

Cпасибо, Mr. Figes!

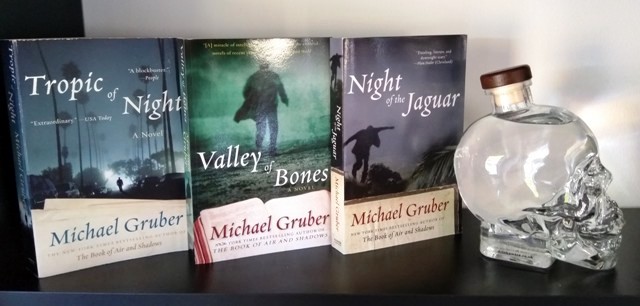

Jimmy Paz novels by Michael Gruber

Great storytelling, magical realism, and a Cuban-American detective in Miami.

What’s not to like?

“She hadn’t fallen in love with a fictional man like this since the day she met Jimmy Paz in the pages of Michael Gruber’s novels. Jimmy was a Cuban detective who could cook and had a weakness for intelligent women.”

(This is a passage from Chapter 19 of my own novel and even though I am not Vera, my character likes some of the same books I do.)

During the past few years I haven’t read many mysteries/thrillers in English because I came up with what I thought was a clever plan: to read books of this genre mainly in foreign languages so that I could get some language practice at the same time. It’s the only way to keep the “books I want to read” list under some semblance of control (Ah, the lies we tell ourselves…)

But one of the exceptions I made was for the Jimmy Paz novels and I ended up reading all

three of them like a woman possessed. Which makes sense since there is magic within the pages.

Jimmy’s mom owns a Cuban restaurant in Miami (where he often helps her out) and—as he eventually finds out—she also practices Santería. So when strange and gruesome murders start happening, things that can’t be explained by logic or science, her knowledge comes in handy during Jimmy’s investigations. In the first novel (Tropic of Night), he also gets help from a woman named Jane Doe who has studied unusual things during her travels in Africa. (Before you begin reading, it might be helpful to know that there’s a glossary of terms at the back of the book.)

The novels were so gripping that there must have been some kind of sorcery involved in writing them. At any rate, Michael Gruber is a wizard when it comes to storytelling, and the Jimmy Paz novels are definitely not your run-of-the-mill mysteries. I’m not exactly sure how to describe them. Maybe literary fiction wrapped around a mystery?

Here are the novels in order:

Tropic of Night

Valley of Bones

Night of the Jaguar

A Doghill History of Finland by Mauri Kunnas

A Doghill History of Finland

by Mauri Kunnas

When my boys were young, I spent countless hours reading out loud to them from Mauri Kunnas books. They literally could not get enough of them, wanting to hear the same stories over and over again.

Luckily all books by Mauri Kunnas are fun for adults as well; both the stories and the illustrations, and they were also my favorite books to read out loud. So much so, that no matter how old I get, I still can’t resist buying them.

A Doghill History of Finland is a colorful and amusing romp through Finnish history, from the 16th to the 19th centuries with the typically delightful illustrations that make up all of Kunnas’ books. It seems that no matter how often you look at the pictures, you always discover something new, and in this one you will also learn something along the way. History does not have to be boring! It was published in 2017, when Finland celebrated 100 years of independence.

I would recommend any and all of the Mauri Kunnas books, they are the cutest children’s books you could possibly imagine.

Oh, and on the last page of A Doghill History of Finland there is a quote from Axel Oxenstierna, a Swedish statesman, taken from a letter he wrote to his son in 1648:

“Oh my son, if you only knew with how little wisdom this world is governed.”

Seems that some things don’t change much throughout the centuries…

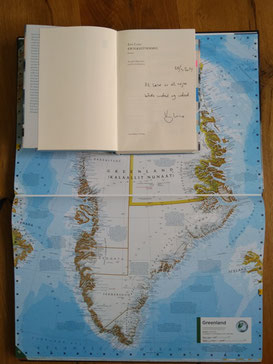

Another Great Danish Novel: Prophets of Eternal Fjord by Kim Leine

After writing last week’s post, I remembered another Danish novel that I really liked:

Prophets of Eternal Fjord by Kim Leine.

I wrote about it in German a few years ago here, after hearing the author read at Slawski, a bookshop in Buchholz, where I used to live.

This epic novel takes place in Greenland in the late 1700’s, where Morten Falck has come as a missionary from Copenhagen, even though he’s actually more interested in the natural sciences and other things than in theology. He preaches the ten commandments yet breaks most of them himself in this wild frozen land where the Danish culture clashes with that of the locals and where not everybody is prepared to accept colonial rule.

I see that my copy of the book is riddled with little sticky notes to mark passages I liked, and the author signed it with the following sentence:

At læse er at rejse både indad og udad.

(To read is to travel, both inward and outward.)

So true!

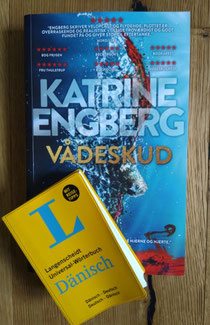

Scandinavian Languages - Nearly Three for the Price of One

This post is for you fellow language learning nerds…

Two years ago I wanted to see if I would be able to read Norwegian on the basis of knowing how to read Swedish, and I found that, with a truckload of time, patience, and effort, as well as a good dictionary, I could.

Now I decided to try the same with Danish. It was slow going at first, and I mean I REALLY just crept along. It took me over two hours to read the first twenty pages of this crime novel, but after that it started getting better.

It’s not that I actually want to learn Danish; I was just curious to see if I could read a simple novel in the language. I guess I needed some kind of mini-challenge for my brain.

Vådeskud by Katrine Engberg is a crime novel set in Copenhagen, actually the fourth in a series. I haven’t read the first three, but that didn’t make a difference. It was easy to follow the story and the main characters are interesting and likeable. These novels seem to be quite popular in Denmark at any rate, and they’ve been translated into many languages.

Since I love to read, this opens up a whole new world of books that I could potentially read in the original. One of my favorite novels is by a Danish author (Smilla’s Sense of Snow by Peter Høeg and beautifully translated into English by Tiina Nunnally) and at university I fell in love with the works of Isak Dinesen (aka Karen Blixen), also Danish.

So … if you’re able to read one of the Scandinavian languages and your brain is also hungry for a bit of a challenge, but not an enormous one, try reading something in one of the other languages. You might be surprised at how much you’re able to figure out in a relatively short period of time, which is, of course, pretty motivating and so increases the chances of wanting to continue. It doesn’t have to be a whole book. You could find an article on a subject that interests you online and start off with that. In my case, I would have to print out the article and read it on paper in a quiet place with no other distractions, because I’m better able to focus on an unfamiliar language that way.

I’m not saying that it doesn’t take patience and effort. It does. But it’s not all that much of a struggle, considering how much work it is to learn a completely new language from scratch. You already have quite a lot to work with in this case.

I would recommend getting a better dictionary than the one I had, though. Mine is a bit meager, as you can see in the photo!

Bad Arguments

An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments

By Ali Almossawi

Illustrated by Alejandro Giraldo

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.”

(Richard P. Feynman)

I bought this book because I fell in love with the cover. The title (Bad Arguments) combined with the adorable illustration was just too irresistible.

Almossawi lists nineteen errors of reasoning and gives examples of them, often with humor, not at all as a stern lecture. Each example is accompanied by a cute illustration showing the thinking fallacy in action.

If you read them closely, you are sure to find examples in the real world showing how all of these bad arguments are used, and chances are, you probably won’t even have to look far. In our house, it’s sometimes the “appeal to hypocrisy”—when you point out that someone’s arguments conflict with their own past (or maybe even current) actions. It sounds something like “Oh yeah, well, YOU do this and that…” And it’s hard to catch yourself when you’re rolling down the “slippery slope argument.”

You can read the book online at www.bookofbadarguments.com in eleven languages (including Finnish! :-)), but it’s much nicer to own a copy because this is one to read through over and over again.

I was going to say that it would be a great book to give as a gift as well, but then again, the receiver might feel offended and think you are telling them that their arguments are bad, which may indeed be the case and that’s why they should read the book.

Hmm…

Ah, but you can couch it like this: say it will help them to see through other peoples’ bad arguments and then hope that they will recognize their own.

Because this book is so decorative, I placed it facing outwards on a shelf so that you

can see the front cover.

p.s. – if all else fails and you run out of arguments, good or bad, you can always revert to this phrase which I saw somewhere: “You may be right, but I like my opinion better.”

What is the meaning of life?

Every Time I Find the Meaning of Life, They Change It.

Wisdom of the Great Philosophers on How to Live

By Daniel Klein

Is life meaningless and everything we do futile?

Well, I don’t have the answers to much of anything in life, but I do know that reading Every Time I Find the Meaning of Life, They Change It by Daniel Klein feels neither meaningless nor futile. Quite the opposite.

I just reread it and loved it just as much as the first time I read it a few years ago. It is charming, amusing, and wise.

Some fifty years ago, Daniel Klein began jotting down philosophical quotes and in this book he goes through them again, adding his own reflections and musings, anecdotes, and memories. He’s able to elucidate complex ideas in an entertaining manner, and the book is worth reading just for the essay on Wittgenstein’s quote alone. And for Derek Parfit’s thought experiments, which may drive you half mad. (Maybe something to bring up at the next dinner party…?) And, and, and—just read the book.

I really liked that the ideas range from one extreme to the other: from the bible to a particle physicist, ancient Greek philosophers to modern day thinkers, hedonism to “Mr. Melancholia” (Schopenhauer).

“The art of life lies in taking pleasures as they pass, and the keenest pleasures are not intellectual, nor are they always moral.” Aristippus

“Life oscillates like a pendulum, back and forth between pain and boredom.” Arthur Schopenhauer

Reading it is kind of a mental roller-coaster ride in the best possible way (meaning that it’s exhilarating, not that it might make you feel ill!). Also, you do not have to know a single thing about philosophy in order to thoroughly enjoy this book; in fact it would be a perfect introduction to philosophical thought. It’s one that can be read over and over again because it feels somehow nourishing for the brain and there’s also something comforting about it.

“Death is not an event in life: we do not live to experience death. If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present. Our life has no end in the way in which our visual field has no limits.” Ludwig Wittgenstein

Notes from Underground

In the Nietzsche biography was a mention that “Dostoevsky made a lightning-strike connection” with Nietzsche when he read Notes from Underground. My brain lit up with an “Oh, I haven’t read that yet!” and this is how my reading pile grows…

I read the Vintage Classics edition, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. It’s a short book, only about 130 pages long, written in 1864, and, according to Wikipedia, it’s one of the first works of existentialist literature.

In the first part, the man in the underground is forty years old and he rants and attacks the world at large in a kind of monologue. He’s filled with loathing for others and himself. But he also philosophizes quite intelligently. In the second part he tells a story about what happened when he was twenty-four and at which point his life was “already gloomy, disorderly, and solitary to the point of savagery.”

This is a somewhat tortuous and intense portrait of a complete outsider in society, but the thing is, he’s smart enough to be completely aware of his actions (he analyzes them every step of the way) yet seems unwilling to change his behavior even as he knows he’s messing things up for himself but still somehow can’t stop himself from doing it. Maybe it would feel different if he were oblivious to the consequences of his actions—but he’s not, and I kept reading with a nearly painfully weird fascination as, for example, he goes to a dinner party where he knows he is unwelcome. It’s a very tormented self-awareness, and a part of him wants to be part of the crowd he so lashes out at, and at times he has wild fantasies about what it would be like to be loved and admired by all.

Do not skip the foreword by the translator, which also gives some background to the story.

A "novel" way to practice French

Of course this isn’t novel in the “new” or “unusual” sense of the word, but literally, with a novel, which is my favorite way to practice reading foreign languages.

La Vérité sur l’Affaire Harry Quebert by Joёl Dicker is such a popular mystery that there’s no need for yet another article raving about it. I just wanted to say that if you’re learning French and you can read YA novels, then you can read this. The language is simple and straightforward, there are no convoluted sentences or abstract concepts which are often hard to understand in foreign languages. I don’t even know French and I was able to read it—with a dictionary, obviously.

Also, don’t be put off by the length of the novel—about 850 pages—but see it as a positive thing because once you get into it, the story will pull you along all the way to the end, and that’s a lot of (entertaining) French practice for just a few euros or dollars!

It took me about two and a half months to get through this because it is mentally taxing to read in a new language (okay, I did move into a new house in between too…)

At first I was only able to read about ten pages at a time, but somewhere around the middle I was surprised to notice that I was reading up to fifty pages an evening before my brain went on strike and refused to continue deciphering the text. Also, the further I got, the less I needed the dictionary. My friend Martina, an avid reader who does know French, surmised that it might be because authors tend to use the same vocabulary throughout their books and so at some point you just get used to it and recognize the words. I think she’s right. And, again, context is the most important key. Give it a try!

More French reading practice: Le buveur d'encre and Practicing Reading French with Childrens' Books

Jung. His Life and Work. A Biographical Memoir by Barbara Hannah

Another deep and influential thinker who’s been hovering around the edges of my life for the past few years is C.G. Jung, and so I thought a biography would be a good way to dip my toes into the water.

Once I’d started Jung. His Life and Work. A Biographical Memoir by Barbara Hannah, I could hardly put it down.

Barbara Hannah (1891-1986) was Jung’s pupil and a lecturer and training analyst at the C.G. Jung Institute in Zürich and she was also a close friend of the Jung family, so the biography felt intensely personal in many ways.

You get a good feel for what kind of person Jung was (remarkable, intelligent, driven, and extremely compassionate), and the themes and ideas he wrote and talked about, even if it’s only the tip of the iceberg. Especially the conscious and unconscious, but also the roles of mythology, religion, dreams, and symbolism, the idea of the anima/animus, to name just a few. His collected works make up some twenty volumes!

I liked the fact that although Jung spent so much time thinking and writing, he was also deeply entrenched in the physical world—his family and friends, patients and pupils, his houses (even building parts of his house in Bollingen)—because that is where we live, after all, that is where we have to put the theories into practice.

If I want to understand anything about psychology and the unconscious mind, then reading Jung seems essential. This biography was definitely a worthwhile read and made me want to find out more. And yes—to explore the shadows as well.

Nietzsche biography

I Am Dynamite! A Life of Friedrich Nietzsche

By Sue Prideaux

“And beware of the good and the righteous! They love to crucify those who make for themselves their own virtues—they hate the solitary man.”

Friedrich Nietzsche, from Thus Spoke Zarathustra

It feels like Nietzsche has been following me around for years—he’s quoted everywhere I turn. However, reading his collected works would require more time and focus than I’m willing to spend at the moment, so I thought I’d start with a biography, and I’m glad I did.

I Am Dynamite! by Sue Prideaux gives a good sense of the times and places Nietzsche lived in. He spent most of his life basically as a vagabond, living at the houses of family or friends or staying at pensions in Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and France. He even had his own room in Wagner’s house. Yet he was both solitary much of the time, spending hours upon hours hiking in the mountains alone and this is when he came up with many of his ideas. He also suffered debilitating ailments that kept him bed-ridden for days, sometimes weeks on end.

I got the impression that Nietzsche was very bold and sure of himself regarding his thoughts and ideas, but that this confidence did not extend to his relations with women. He never married, although twice he did make somewhat spur of the moment proposals— and was rejected both times. (“And beware also of the grip of your own love! The solitary man extends his hand too quickly to those he encounters.” Thus Spoke Zarathustra)

But he was also riddled with doubt and anxiety at times. And no wonder, considering that he attacked many (most?) of the morals and ideas of the times—people don’t really like that, do they? Still, his confidence in his own ideas was so great, that even though his books hardly sold, he wrote that he would be understood at some point in the future—which is exactly what happened.

I pretty much tore through the book in a few days because it was so well written and because Nietzsche was such an extraordinary character. His sister Elisabeth horrified me though, and reading about her was like being in the middle of a soap opera. A rabid anti-Semite, she manipulated, schemed, and told the most outrageous lies.

Sadly, it wasn’t until after he went mad that he became popular and his books began to sell, so he never reaped the benefits. Elisabeth did though, in a frightening manner. It was heartbreaking to read about his last years when he was kept locked up, first in an asylum, and then in an upstairs room in his family’s house.

Nietzsche influenced a great many artists, writers, and intellectuals in Europe in the 1890’s—and here I had to stop reading and look up Edvard Munch’s painting of both Nietzsche and Elisabeth. Apparently, “The Scream” was also inspired by Nietzsche’s writings.

Many bits and pieces of Nietzsche’s writings and letters are included in the book and you get a good sense of the themes that occupied his thoughts. But as far as I can tell, it seems difficult to order Nietzsche’s philosophy into a neat and clear package, because his writings appear to go all over the place. So for the time being, I will content myself with the aphorisms and short but profound commentary taken from various books. That’s enough food for thought for a very long time.

See also: When Nietzsche Wept, a novel by Irvin D. Yalom

More great biographies:

Brutally Finnish and brutally funny advertisement

Imagine the founder of a company walking naked through the fields while talking about their products. It wouldn’t be a German company, that’s for sure…

Click on the link and then on the video near the top of the page, the one titled

“Kyrö Distillery: Presented by a naked man”.

I’ve tasted their gin (“Finnish summer in a bottle”) and it’s good, and I’m looking forward to sipping the whisky (“rich and sophisticated, so you don’t have to be”).

They Know Not What They Do. A novel by Jussi Valtonen

They Know Not What They Do

A novel by Jussi Valtonen

(Original: He eivät tiedä mitä tekevät)

Joe Chayefski is an American professor of neuroscience, whose life gets turned upside down because he didn’t know what he was doing, did not realize the consequences of his actions or lack thereof—and nobody else really knew what they were doing either.

Twenty years ago he spent a few years in Finland and had a son with a Finnish woman, but he left them and didn’t keep in touch, only sending a card once a year. But his son Samuel did not forget him, and now Joe’s past is messing up his life in ways he never could have dreamed of.

And what is this new iAM device that his daughter comes home with one day? The one where you don’t need to tap or click any buttons, that doesn’t have a screen, that can literally read your thoughts and provide you with content as fast as you can think? What is the company behind the device really up to at the school? And what are these little neuro optimizer pills he finds in her purse? And who broke into his lab and is terrorizing his family and why?

Jussi Valtonen is an absolute master at describing characters, how people feel and how they justify their behavior. It was literally a joy to read, for the language alone, and I often found myself smiling at how he’d phrased something so eerily well. How Joe views Finns and what the Finnish characters think about Americans, made me laugh because I’ve heard them all too, from all sides, so the author definitely got that right. (Still, I do want to mention that in the novel, Joe is in Helsinki in the early 90’s and the city has changed a lot since then!)

Valtonen tackles seemingly everything on every level, big and small themes, all rolled up into an entertaining story that keeps you hooked.

Consequences of past actions. Misunderstandings that last for years. Personal relationships, moral dilemmas, cultural differences, technology, and social media. How things aren’t always what they seem to be. Are they ever, really? And how do you even define that?

It’s a work of fiction, but it’s deep, and it will make you think about a thing or two during and after reading it. Just the kind of story I like.

I can’t say anything about the translations, but I assure you that the Finnish original is fantastic. In fact, He eivät tiedä mitä tekevät won the Finlandia Prize in 2014, the most prestigious literary award in Finland.

The English title is They Know Not What They Do and in German it’s Zwei Kontinente. I assume it’s been translated into other languages as well.

He eivät tiedä mitä tekevät has been on my shelf for years, so long that I had no idea what it was even about. But, wanting to read something in Finnish, I plucked it from the shelf without a moment of hesitation, somehow sure that this was it. Maybe I liked the title. Or the fact that it looked nice and thick. Since I’ve been reading non-fiction books about the brain and have been listening to a neuroscience podcast, it felt like a very weird and wonderful coincidence to have pulled out just this book, in which the main character is a neuroscientist.

You can change your brain

The Brain that Changes Itself

By Norman Doidge

Neuroplasticity is something I am nearly obsessed with these days.

Almost everyone I know, myself included, wants to either learn something new or change some behavior.

But how many times do we say “I can’t”, “I could never do…”, “I’m just not good at…”, “this is just the way I am” or some other variation of these?

I’m in the process of proving myself wrong on a number of these things and so I know the value of neuroplasticity firsthand—even though, as I write, Word is trying to tell me that there’s not even such a word as neuroplasticity and insists on underlining it in red. (I have a really old version of Word, so maybe the newer ones have caught up with the science…)

Okay, so the things I’m learning are small in comparison to the mind-boggling transformations Norman Doidge describes in The Brain that Changes Itself: how people with strokes can learn to speak and move again, how a woman who was literally born with only half a brain is able to function in life, how learning problems can be solved, what we can all do to keep our brains healthy, and so much more. He also writes about the scientists who worked on figuring out all of this. Most fascinating to me is how your thoughts can literally change your physiology.

Also, there is no such thing as being too old for this; we can learn new things until the day we die. Maybe not as effortlessly as an eight-year-old, but hey, you probably have some other advantages in life now, that you didn’t have when you were eight!

The Brain that Changes Itself is captivating and inspiring, and after reading it, it feels as though both the world and your own mind are filled with exciting possibilities.

Another great book about the brain is 7 ½ Lessons About the Brain

When Nietzsche Wept by Irvin D. Yalom

When Nietzsche Wept by Irvin D. Yalom

You must be ready to burn yourself in your own flame: how could you become new, if you had not first become ashes?

—Friedrich Nietzsche

Thus Spake Zarathustra

When Nietzsche Wept is a novel written by psychiatrist Irvin D. Yalom (Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Stanford University), and it weaves together a story of psychology, philosophy, Nietzsche, and fin-de-siècle Vienna, all fascinating subjects unto themselves.

Yalom’s colorful descriptions drop you right into the Vienna of 1882 when Franz Joseph I was emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, psychotherapy was just being discovered, and Freud was a 26-year-old medical student.

In the novel, the bewitching Lou Salomé persuades Doctor Josef Breuer to take Nietzsche on as a patient to cure his despair. “The future of German philosophy hangs in the balance,” she writes.

Breuer manages to do so, and an interesting relationship develops between him and Nietzsche, one that he often discusses with young Freud. And this is what I liked most about the novel, all the psychological and philosophical conversations between the characters, their observations and questions about human nature.

Josef Breuer, Sigmund Freud, Friedrich Nietzsche, Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth, Breuer’s patient Anna O., Lou Salomé, Breuer’s wife Mathilde and their five children, Paul Rée—they all existed, although Breuer and Nietzsche never actually met in real life, so the novel is a blend of fact and fiction. Yalom also adds a note at the back of the book detailing which is which.

I devoured this story, but I didn’t literally chew on the book. That was Indy when he was still a puppy and was developing a taste for literature.

My Daily Dose of Stoic Philosophy

I just moved from a house we’d rented to the house we’ve been building, and the only book I had time to read during the moving phase was The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman.

This book is oh so good!

I’m reading through it a second time now, one page every day, because that’s how it’s set up. For each day of the year there’s a quote from either Epictetus, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, or another philosopher, accompanied by an explanation or commentary.

Each month also has a theme; June’s was “problem solving,” which is something one needs to do a lot during the last phases of constructing a house and moving—especially when you move an entire household on your own without a moving company.

My favorite page was from June 8th: the heading for the day was “Brick by boring brick” (you see how apt that was!) and the quote for the day was from Marcus Aurelius:

You must build up your life action by action, and be content if each one achieves its goal as far as possible—and no one can keep you from this. But there will be some external obstacle! Perhaps, but no obstacle to acting with justice, self-control, and wisdom. But what if some other area of my action is thwarted? Well, gladly accept the obstacle for what it is and shift your attention to what is given, and another action will immediately take its place, one that better fits the life you are building.

—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 8.32

I read that page multiple times…

On January 1st I sent my sister a photo of the December 31 page, which is titled “Get Active in Your Own Rescue,” and a few hours later she’d ordered herself a copy based on that one page! Since then, we’ve had numerous WhatsApp conversations about The Daily Stoic, mentioning quotes we liked or thought were especially relevant, and—maybe because we live so far apart, she’s in Southern California and I’m in Northern Germany—there’s something very pleasurable about knowing that we’re reading the same texts every day.

Practicing reading French with Children's Books

Practicing languages has helped keep me sane during this interminably long lockdown in Germany. Something about learning a new language is both invigorating and calming for me—although probably not both at the same time.

I've been teaching myself to read French. It’s purely passive learning, but it’s better than nothing, and I haven’t given up hope that in-person language classes will be a reality again soon. I’ve been slowly working my way through children’s books because I find that context is the most entertaining way to learn. It also feels different to read a “real” book written for children than it does to read texts for beginners in language books, and the stories are much better.

It takes me forever to get through even a short children’s book, and my dictionary’s already starting to fall apart at the seams (yes, I use a paper dictionary). Sometimes I can get through multiple paragraphs without having to look anything up, which is the magic of context. You don’t have to know every single word in order to get the meaning, but this also means you have to experiment a little, try out different texts to see what the right level is for you.

Pressfield's War of Art

The War of Art by Steven Pressfield

Projects you want to do but can’t get started on?

Procrastination problems?

Peeved with yourself because of the above?

Pressfield has written the book for you.

If you’ve ever spent an hour or two scrolling through blogposts about procrastination (who, me?) instead of starting on a project you need or want to do, then this is the book for you.

Steven Pressfield has a name for all the excuses, justifications, and rationalizations—both conscious and subconscious—which we use to justify why we “can’t” do something.

He calls it Resistance.

While he uses writing as an example of how resistance sabotages our plans, it’s applicable to anything we want to do, be it starting a new exercise regime or a new business.

Pressfield is tough and raw, but also kind and nonjudgmental. He’s been there. He’s speaking from experience. In the first part of the book he lists every form of Resistance out there. He sees through all the bullshit. His own and mine and probably yours as well.

An Antidote to Self-Pity

He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how. (Nietzsche)

So many people talk and write about the importance of having meaning or purpose in one’s life, but so far nothing I have heard or read has been as impactful as what Viktor Frankl wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning. In his case, this literally saved his life. For most of us these days, it might mean the difference between actually living, and just trying to get through the day.

Viktor Frankl was a Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry in Vienna, and he also survived three years in concentration camps during World War II, including Auschwitz and Dachau.

Man’s Search for Meaning, his most popular book, was first published in 1946. It’s both an easy read and a tough read.

Chatty Neurons

7 ¹/₂ Lessons About the Brain

By Lisa Feldman Barrett

Right off the bat, Dr. Feldman Barrett tells us that our brains are not made for thinking.

What?

Well, I’m sure we can all come up with a few people for whom that certainly appears to be true …

I won’t tell you what she says it’s for though—you’ll have to read the book to find

out.

Dr. Feldman Barrett dispels some myths about how the brain works and says that many of the metaphors used to explain the mind are often mistaken for actual brain structures.

That said, the author uses many helpful metaphors herself (always pointing out when

she’s doing so) to explain how the brain is wired into a network of neurons that constantly chat with each other. Having read her descriptions, I can now better understand how this incessant

communication can also lead to gossip being spread around in your mind—you know, all those things you thought were true, but maybe aren’t, after all. (“You’re not good at learning this or that”

being one of the most widespread. Time to do some fact checking because that could just be fake news that spread like wildfire throughout your neuronal network while you were growing

up.)

Fascinating too, how the brain can make predictions on what will happen and adjust your

physiology accordingly. For example, I did not know that it takes water 20 minutes to reach the bloodstream. So why does my thirst feel quenched almost immediately after I have had a glass of

water? Read Lesson 4 (Your Brain Predicts (Almost) Everything You Do) to find out.

I wish all politicians and decision-makers would read this book, especially Lessons 3

(Little Brains Wire Themselves to Their World), 5 (Your Brain Secretly Works With Other Brains), and 7 (Our Brains Can Create Reality) and then take action based on this information.

All in all, this short book (just 166 pages, including the appendix which is also well worth reading) will make you think about human behavior, especially your own. (Dr. Feldman Barrett does NOT claim that we don’t think, because obviously we do, it’s just not the primary function of the brain.)

Ink Drinker

Last month I saw the term buveur d’encre on a list of translations for bookworm in different languages. My dictionary only had one translation for bookworm and that was rat de bibliothèque, so I googled buveur d'encre and pictures of this book came up.

A few days later, a copy of Le buveur d’encre by Éric Sanvoisin & Martin Matje showed up in my mailbox.

Inexplicable, really.

Buveur d’encre means ink drinker and I think it’s a fabulous term!

Also, I am teaching myself to read French, so this little book (for ages 7 and up) was the perfect resource.

My grasp of the language is still weak, so it took me some time to read it and I definitely needed my dictionary, but I wanted to know what happened. Most language book texts are rather dull and I need to practice with something that keeps my interest. I find it nearly impossible to stay motivated when I don’t really care what the next sentence is.

Odilon is a young boy who hates books and whose bibliophile father owns a bookstore. One day, a strange customer floats in and begins to drink out of a book using a straw, and so Odilon decides to follow him even though he’s scared.

And then … oh, but the book is only a few pages long, so I’ll stop here so as not to write in any spoilers.

So, if you are looking for a book for a budding ink drinker, this is it. I noticed that there is a whole series of them, nine at least. And I loved the illustrations as well.

Also, I just realized that what a great excuse (as

if one would even need one!) to buy cute children’s books even after your own kids have moved out—you just read them in a foreign language and so they count as language resources. Serious

business.

J’adore ce livre!

Happy ink drinking :-)

p.s. – this series is also available in English

Finnish Characters and a Blueberry Pie Recipe

Predictably, a few Finnish characters found their way into my novel, An Unconventional Marriage …

Elsa, the woman who Vera observes plunging into the icy water at the beach; Jukka, the hunky “Nordic god”; and his cousin Mia, who knows how to fly a helicopter but doesn’t know how to make coffee. Jukka is a chef, and during the story, Vera bakes a blueberry pie using one of his recipes.

In August, a friend of mine sent me a message saying that she was out picking blueberries and would I please send her my blueberry pie recipe (that’s how I knew she was reading my book). Unfortunately we were busy moving and I had packed all my recipes away already, so I found the traditional Finnish recipe on the internet and translated it into German for her.

I have decided to give you my sister’s version—she tweaked it a little and converted it into US measurements. I will mention that one of the many fabulous things about my sister Marjaana is that she has a culinary school degree and knows her stuff when it comes to food and recipes. Not only that, this version was printed in Sunset magazine some years ago!

The original recipe calls for the Finnish dairy product kermaviili, a curd cream made with buttermilk culture which is near impossible to find outside of the Nordic countries. Fortunately, sour cream works just as well, as do Schmand and Quark if you are in Germany.

Hyvää ruokahalua, Guten Appetit, and enjoy!

An Unconventional Marriage - A Novel

An Unconventional Marriage

by Liisa Rinne

A humorous and irreverent novel about the difficulty of long-term monogamy.

Vera cherishes the comfort and security of her family life and she is deeply attached to her husband Ben. It’s not a bad marriage, but the sparks are gone and they are more like buddies than lovers.

At 48, Vera feels too young to resign herself to a future with no promise of passion, hot sex, or the thrill of a new relationship ever again.

Some people divorce, some have affairs, and others just plod along and pretend everything is fine. But what if there was another, less conventional alternative?

When Vera suggests they try out an open relationship, Ben is at first shocked and then intrigued. As Vera’s friend Rita points out, what man could resist being “allowed” to have sex with other women?

However—Vera knows that this will only work if Ben has a lover before she does and so she sets out to find one for him. This turns out to be more complicated than she had anticipated, and along the way she has a few unexpected adventures and discovers things about herself that she has kept buried for years.

Booklover's Paradise: Frankfurt Book Fair 2018

Walking onto the grounds of the Frankfurt Book Fair each year is exciting. It’s like entering an enormous treasure chest glittering with new publications. You rush around from stand to stand, seduced by beautiful book covers and posters advertising the clever new book by your favorite author. Each volume you greedily reach for might hold the promise of hours of entertainment, knowledge, innovative ideas, or that piece of wisdom you’ve been searching for all your life.

It’s exhausting but fun. The Frankfurt Book Fair is colorful and lively, buzzing with publishers from all around the world, readings, live interviews, authors signing books, food trucks and coffee stands, booklovers milling around or sitting in armchairs completely engrossed in some new find, and I love the fact that there are cosplayers in fantastic costumes everywhere. The atmosphere is casual and friendly – you rarely see a grumpy face there. (At least not on the weekends when the general public is allowed in…) If you should get tired of looking at books, you can always escape to the Gourmet Gallery, Stationery and Gifts, or Calendar Gallery. The Self-Publishing area seems to grow each year as well.

To-do lists à la Leonardo da Vinci

Walter Isaacson

Leonardo da Vinci. The Biography

Most of us make to-do lists, but I would bet that hardly anyone has items such as “Draw Milan”, “Get the master of arithmetic to show you how to square a triangle”, or “Describe the tongue of a woodpecker” on it. Mine certainly don’t. But Leonardo da Vinci did, and these are just a few of the numerous examples scattered throughout this fascinating biography.

The author, Walter Isaacson, used Leonardo da Vinci’s countless notebooks as his starting point. I can’t even imagine how much time he must have spent sifting and reading through the over 7,200 pages crammed with notes, sketches, anatomical drawings, calculations, riddles, ideas for weapons and fortifications, lists (including lists of all the books he owned and wanted to have!), and pretty much everything else under the sun.

"I cannot live without books."

The quote above is from Thomas Jefferson.

J. Kevin Graffagnino

Only in Books: Writers, Readers, & Bibliophiles on Their Passion

“Without disparaging the other forms of collecting, I confess a conviction that the human impulse to collect reaches one of its highest levels in the domain of books.” Theodore C. Blegen (1891 – 1969)

Not that booklovers need an excuse for overflowing shelves, stacks of books on windowsills blocking the sunlight, or the myriads of to-be-read piles scattered about the house – but if you are in need of moral support, Only in Books will provide more than enough. This is what I turn to over and over whenever I need a good quote about books and reading.

I’m not sure how many quotes are collected here, but it’s a treasure trove, especially for those who think like Samuel Pepys (1632 – 1703) who said:

“I know not how to abstain from reading.”

And should you have a spouse who complains about the money you spend in bookstores, remind him or her that a book costs less than a few beers in a bar and certainly cheaper than a pair of shoes or a cordless drill.

“No entertainment is so cheap as reading, nor any pleasure so lasting.”

Mary Wortley Montague (1689 – 1762)

And if the argument above doesn’t work, here’s one to ponder:

“Reading goes ill with the married state.” Molière (1622 – 1673)

And just imagine the shitstorm that would ensue should anyone today utter the following in public!

“I am persuaded that foolish writers and readers are created for each other; and that Fortune provides readers as she does mates for ugly women.”

Horace Walpole (1717 – 1797)

I’ll stop now, before I end up re-printing the entire book here. But I have to end with a quote from Oscar Wilde (1856 – 1900). This is for you writers out there. :-)

“The play was a great success. But the audience was a failure.”

A lost city, an ancient curse...

The Lost City of the Monkey God by Douglas Preston has all the ingredients of a great adventure story. A dense jungle far from human habitation, where one could easily get lost by just wandering a few meters away from the camp, disease-bearing insects, close encounters with fer-de-lances, (large, aggressive, venomous snakes), in short a place where the team was equipped with two former SAS soldiers whose job was to ensure their survival. A lost city somewhere in the jungles of Honduras, known as the Lost City of the Monkey God or Ciudad Blanca (White City) which until then had been nothing more than a myth, a story passed down through generations. Oh, and to top it all off, the city was said to be cursed. Sounds like I’m describing a Hollywood film, doesn’t it? But this is the true story of an expedition that took place in 2012.

Babel No More

Michael Erard

Babel No More. The Search for the World's Most Extraordinary Language Learners

Babel No More by linguist Michael Erard won’t teach you how to learn a new language, but it will certainly motivate you to “apply the seat of your pants to the seat of your chair”, grab that grammar book and dictionary, and start learning. Scattered throughout the book are a few pointers given by various hyperpolyglots (in the book the term was used for people who knew at least eleven languages) and at the back of the book are two pages with answers from an online survey in which Michael Erard asked people for their top three methods for learning languages.

But this book is mainly a trek across the globe and into the past in search of historical and living hyperpolyglots. There’s the Italian Cardinal Giuseppe Mezzofanti who was said to speak 72 languages in the 19th century, the cranky German diplomat, Emil Krebs (1867 – 1930), who was said to know over sixty languages, and the Hungarian translator Lomb Kató (1909 – 2003) who at 86 years of age was learning Hebrew as her seventeenth language, and a multitude of other interesting characters.

Language learning by reading

The most effective way to learn a language is to use it as much as possible. Speaking is preferable. But what if there’s nobody around to talk to in your new language? Or if you simply don’t like the thought of skyping with strangers in order to practice? My primary objective in learning Swedish is being able to read. This may change at some point, but it’s what I’m concentrating on at the moment.

In March I bought a Swedish magazine and – being opimistic – Häxan by Camilla Läckberg. (English translation: The Girl in the Woods)

I had practiced about 20 hours of Swedish when I started trying to read the magazine. Normally I never buy magazines because they are filled with advertisements, most of the articles are too short and rather trivial, and when I’m finished reading, the magazine gets tossed or given to a friend.

But funnily enough, the very reasons I don’t buy them make them a perfect language learning tool!

You can highlight words and phrases and jot notes onto the pages. I don’t do this with books. Ads are a great way to learn important new words like ‘anti-rynkkräm’ (anti-wrinkle cream), fuktighetsgivande (moisturizing) and stiliga stövletter (stylish ankle boots). Short trite phrases and loads of photos make it easy to understand what’s meant. I literally read the entire magazine, ads and all and I doubt there’s another woman out there who has spent so many hours poring over this particular issue of Femina! There’s a huge range of subjects to learn vocabulary from because these are frequently used words and phrases, you can see how sentences are structured, and the grammar is fairly simple and up-to-date. (Remember, you should probably not look for the equivalent of The Economist right in the beginning!) Specialty magazines would be fun to use too – sailing, outdoor, equestrian, cooking, and so on, if you are interested in a particular subject and want to learn the related vocabulary.

Re-learning a language (Swedish)

The reason I haven’t posted anything for ages is because I have spent the past 3 months obsessed with re-learning Swedish. After learning it nearly thirty years ago, I haven’t used it since, so maybe re-learning isn’t the right word. At the beginning it felt like I was starting nearly at square one again. Regarding the brain in general, there’s the saying „use it or lose it“and this applies especially to languages. If you don’t work at maintaining what you’ve learned, it will gradually rust away. So why Swedish?

Because I was irritated with myself for having let it rust away. Last time I moved, I found Tove Jansson’s Bildhuggarens Dotter and realized that I had been able to read it once upon a time, but was no longer able to do so, and it’s not even a very complicated text.

For some reason I had always believed that I don’t have the self-discipline to teach myself a language, that I’d always need a classroom to learn. And now I live in a place where there are no suitable language classes close by. So I plan on proving myself wrong!

My goal is to be able to read Swedish novels in Swedish by the end of 2018. I must have at least 50 books on my shelves that have been translated from Swedish into English or German, and I have decided that if I want to re-read them, I will do so in Swedish.

From Here to Eternity

From Here to Eternity.

Traveling the World to Find the Good Death

By Caitlin Doughty

From here to Eternity felt like perfect travel reading for a trip to Helsinki in March to attend a memorial service.

The author, Caitlin Doughty, is a mortician who runs a non-profit (!) funeral home called Undertaking in L.A., and she has written a witty and thought-provoking book about funerary customs around the world and through history. What she describes here is not even remotely like the customs I have experienced in the USA, Germany, or Finland. She has traveled to Indonesia, Belize, Bolivia, Mexico, Japan, and Spain to see how other cultures take care of their dead. And maybe those are the key words here. We don’t take care of our dead. As soon as somebody dies, they are handed over to a funeral home, i.e. a company, because we wouldn’t know what to do anyway. We haven’t learned anything about this.

Contrast this with the place in Indonesia which she visited, where the dead are kept in their families‘ homes for the period of time between their death and the funeral. (This can range from several months to several years!) There are descriptions of an open-air pyre in Colorado, a facility in North Carolina which is experimenting with turning bodies into compost, an un-embalmed natural burial in California (I’ve often wondered why all burials aren’t like that, it seems much more natural), a hypermodern funeral home in Barcelona, a high-tech columbarium (building which stores cremated remains) in Japan, and ñatitas (human skulls or mummified heads) in La Paz, Bolivia which are revered and thought to be able to grant certain favors.

My favorite ritual is the Días de los Muertos celebrated in Mexico. I wish we had something similar here. I love the idea of going to the cemetery in Helsinki with my whole family, bringing food, drink, and candles, decorating the place with bright flowers and hearing a band playing in the background. I’m pretty sure my aunts would be pleased by the idea too. The cemetery officials in Helsinki probably less so…

Despite the subject matter, From Here to Eternity is anything but a somber and morbid read. It’s written with a healthy and lively dose of dark humor and I hope it gets translated into many languages! After all, it’s a subject that affects each and every one of us sooner or later, and of course reading it makes you think about your own mortality and how you want to be ‚interred‘ when the time comes.

Fun Finnish Stuff

“Finnish is sooo hard to learn!”

I couldn’t even count the number of times I’ve heard that phrase (strangely enough, mostly from people who’ve never even made an effort to find out if that is true or not.)

Well, maybe it is, but learning English has its difficulties as well, especially when it comes to colloquialisms. Here’s a link to a YouTube video of the Finnish comedian Ismo Leikola on the Conan O’Brien show in January, explaining why the word “ass” is the most difficult word in the English language. (Apparently the video has spread like wildfire!)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RAGcDi0DRtU

Dobelli's Toolbox for the Mind

View these books as a mental toolkit, a compendium of ideas from philosophers, psychologists, scientists, and economists. Tools to help one make better decisions and to become aware of what sort of “thinking errors” are most common. Some ideas have been around for ages (from Seneca, Boethius, and other Stoics), but he also includes modern theories by Daniel Kahnemann, Warren Buffett, and Charlie Munger, to name just a few.

Just as you don’t need every tool in a well-stocked toolbox, you probably won’t need each one of these mental tools. I don’t agree with each and every one either, but they will certainly make you analyze how you make decisions or behave in certain ways.

Bookshops in Taiwan

Now, how cool is this? It seems I have a foreign correspondent in Taiwan!

In between hanging out at local bookstores, our lovely, intelligent, and altogether lovable niece is studying there at the moment. She is one of those rare and brave German girls who has been learning Chinese since seventh grade, and is at HSK Level 3 * now.

Harry Potter will always be one of her most-loved book series, but recent favorites include The Raven Boys by Maggie Stiefvater and Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World by Cal Newport (which she doesn’t really need, diligent as she already is…)

* Test takers who are able to pass the HSK (Level III) can communicate in Chinese at a basic level in their daily, academic and professional lives. They can manage most communication in Chinese when travelling in China. (from: China Education Center Ltd.)

A magic mushroom of a novel... The Man Who Died by Antti Tuomainen

Some books hook you right from the first page.

Mies joka kuoli by Antti Tuomainen hooked me before I even opened the book, just because the premise is so unusual.

Here is a translation of the back cover of the Finnish original, so you can see what I mean:

A murderously fun thriller about love, death, betrayal, and, of course, mushrooms.

Jaakko Kaunismaa is a successful 37-year old mushroom entrepreneur who receives surprising and shocking news from his doctor: he is dying. Further tests reveal that he is the victim of long-term poisoning – in other words, somebody is murdering him, slowly but surely.

Bibliomysteries - A perfect gift for booklovers

Bibliomysteries – A perfect gift for booklovers

“What treats you have in store!” – Ian Rankin

Ian Rankin’s quote on the front cover of this deliciously fat volume is so true!

Even if you’re not generally a fan of short stories, these lethal literary tidbits are perfect for long dark winter evenings. Not so hair-raising that you can’t fall asleep afterwards, and can be read when you’re alone in the house with the wind howling outside.

The stories are diverse, set in different epochs, countries, and social situations. For example, one is about a Mexican drug lord whose weakness for first editions becomes his undoing. Sigmund Freud has an uncomfortable encounter in another. A magical library changes the life of Mr. Berger in John Connolly’s story, and a private detective searches for the book carrying a dead Mafia Boss’s secrets in It’s in the Book by Mickey Spillane & Max Allan Collins. Also, book club members may not be as innocuous as one might assume…

There are fifteen short stories set in the world of books and bookstores, written by renowned authors exclusively for the Mysterious Bookshop in New York City and edited by its owner Otto Penzler. I checked out the Mysterious Press website and saw that there are many more bibliomysteries available, mainly as e-books though. I hope that Mr. Penzler will bring out a second volume of collected bibliomysteries very soon!

Murderous delights for your favorite booklovers - be sure to start with yourself!

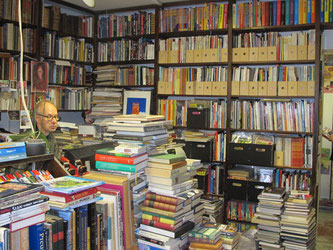

Superb Antiquarian Bookshop in Helsinki - Kampintorin Antikvariaatti

In Helsinki I had a few hours before my flight, so I set off to explore some antiquarian bookshops. Actual shopping was not really feasible since my suitcase was already full, including six books (in my defence – three of them I’d received as gifts), Pentik bowls and towels, rye bread, and probably a kilo of chocolate among other things. But one can always just browse, right? One of the books in my suitcase was Koiramäen Suomen Historia (Doghill's History of Finland) the newest one by Mauri Kunnas – one can never be too old and jaded for these, they are great fun for kids and adults alike - and since Finland is celebrating 100 years of independence on December 6th this year, it did not seem like an option to not buy it!

Originally I’d planned to visit at least three or four second-hand bookshops, but then I walked into Kampintorin Antikvariaatti (centrally located at Fredrikinkatu 63) and I was sold.

A perfect day in Frankfurt

Frankfurt has much more to offer than just a fabulous Book Fair each October. Christiane (my sister-in-law) has lived in Frankfurt all her life and she planned a perfect day on Friday before the fair.

We started off with literature/culture and toured the Goethe-House which is definitely worth a visit. This is where Johann Wolfgang Goethe was born on August 28, 1749 (supposedly just as the clock struck twelve noon). It’s a spacious house with four floors and there are nice descriptions of what each room was used for. It’s easy to picture Goethe in the writing room, hunched over his early manuscripts at the desk or standing at the high desk, his pen (quill?) scratching across the paper, line after endless line. In the library filled with leather bound volumes, Christiane and I noted that there were books in at least four different languages: German, Latin, French, and English. Goethe’s father had collected about 2,000 books in all different fields of study.

After we’d filled our minds, we needed a little something for the body; luckily, the Bitter & Zart Salon was just a few minutes walk away. Coffee and a slice of decadent dark chocolate raspberry cake worked miracles. The atmosphere is as luscious as the cakes and their adjacent shop is full of chocolaty temptations.

Notes from the Frankfurt Book Fair 2017

Anyone trying to squeeze their way through the crowds at the Frankfurt Book Fair each October would be inclined to disagree that the printed word is losing ground. For my sister-in-law Christiane and me, the annual book fair is part pilgrimage to a holy site and part intense but enjoyable work (we most certainly don’t come here to play ;-))

The Frankfurt Book Fair is huge and the first few hours are overwhelming – we’re like kids set free in Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, psyched but also a little edgy. How on earth will we get through this all in just two days? “This” meaning some 7000 exhibitors from over 100 countries presenting about 400,000 titles. Of course we’re only interested in a fraction of the wares, but it takes time to get from stand to stand when you’re sharing the space with 100,000 other visitors (and this is only the approximate number of general public visitors on Saturday and Sunday. The total including the trade visitors is somewhere around 270,000 for all five days!)

Hour by hour, as our lists steadily grow, our legs and feet begin to tire, it’s too hot in the halls, I forgot to bring a water bottle, and we get annoyed with feverish fans blocking the aisles waiting for autographs from some author with rock star status. Yet it doesn't matter - I wouldn’t miss it for anything in the world! Events, interviews, author readings, a self-publishing area, indie publishers, digital media – it’s all there. But the main focus is still the printed book. This is our idea of a perfect weekend.

Packing books for a move

Each time we move, some visitor inevitably stands in front of my bookshelves with an expression of horror, imagining that it will take me days to pack all my books. Lest you think I live in an immense library, there are only about 2500 books in the house, including all the children’s and YA books – so maybe just slightly more than in the average household…