He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how. (Nietzsche)

So many people talk and write about the importance of having meaning or purpose in one’s life, but so far nothing I have heard or read has been as impactful as what Viktor Frankl wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning. In his case, this literally saved his life. For most of us these days, it might mean the difference between actually living, and just trying to get through the day.

Viktor Frankl was a Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry in Vienna, and he also survived three years in concentration camps during World War II, including Auschwitz and Dachau.

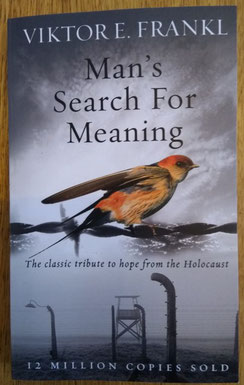

Man’s Search for Meaning, his most popular book, was first published in 1946. It’s both an easy read and a tough read.

Easy because it’s short (this edition is only 154 pages long) and clearly written.

Tough because all accounts of life in concentration camps are shocking and emotionally rattling. No matter how often you read about this, it’s still hard to believe that humans can behave this way towards other human beings.

Tough because while reading this book, there comes this realization that you are literally out of excuses and that the only person responsible for your life is you. And in comparison to what he went through, most of our “problems” are mere inconveniences.

The book is divided into three parts:

- Experiences in a Concentration Camp

- Logotherapy in a Nutshell

- The Case for a Tragic Optimism

Logotherapy is “meaning-centered psychiatry,” and the tragic optimism refers to how to retain meaning in life despite tragedy and suffering that one cannot change. He ties all three parts together using examples from his experiences in the concentration camps to illustrate his points in the other parts of the book.

Frankl maintains that humans need something to strive for and that if they don’t have anything, there might be an inner void, an existential vacuum that is far worse for the psyche than if one is struggling to reach something which is meaningful to oneself.

One of the many anecdotes that caught my attention was the one in which Frankl describes how they knew that a prisoner in the camp would die soon. Refusing to get up and work and then smoking their cigarettes instead of saving them to trade for a bowl of soup—opting for immediate pleasure because they had given up on any idea of a future—was a sure sign.

My son Max underlined this same passage in his copy of the book. One of his biggest takeaways was that only you are responsible for how you think and act, no matter what circumstances, and this cannot be taken from you. This is one of the main principles of Stoicism as well, and Viktor Frankl put that into practice better than most. A true role model.

There is more packed into this slim volume than in many books twice as long and it is a book to read and reread. I can’t think of anyone I wouldn’t recommend it to.

Thank you to my sister Marjaana for the title of the blogpost!

Write a comment